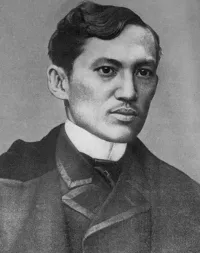

In honor of two Filipino painters, Rizal's toast to Luna and Hidalgo

(English translation of the full text of Rizal's speech at a banquet in honor of Juan Luna and Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, Madrid, Spain, June 25, 1884)

In rising to speak I have no fear that you will listen to me with superciliousness, for you have come here to add to ours your enthusiasm, the stimulus of youth, and you cannot but be indulgent. Sympathetic currents pervade the air, bonds of fellowship radiate in all directions, generous souls listen, and so I do not fear for my humble personality, nor do I doubt your kindness. Sincere men yourselves, you seek only sincerity, and from that height, where noble sentiments prevail, you give no heed to sordid trifles. You survey the whole field, you weigh the cause and extend your hand to whomsoever like myself, desires to unite with you in a single thought, in a sole aspiration: the glorification of genius, the grandeur of the fatherland!

|

|

| (Dr. Jose P. Rizal) |

Such is, indeed, the reason for this gathering. In the history of mankind there are names which in themselves signify an achievement-which call up reverence and greatness; names which, like magic formulas, invoke agreeable and pleasant ideas; names which come to form a compact, a token of peace, a bond of love among the nations. To such belong the names of Luna and Hidalgo: their splendor illuminates two extremes of the globe-the Orient and the Occident, Spain and the Philippines. As I utter them, I seem to see two luminous arches that rise from either region to blend there on high, impelled by the sympathy of a common origin, and from that height to unite two peoples with eternal bonds; two peoples whom the seas and space vainly separate; two peoples among whom do not germinate the seeds of disunion blindly sown by men and their despotism. Luna and Hidalgo are the pride of Spain as of the Philippines-though born in the Philippines, they might have been born in Spain, for genius has no country; genius bursts forth everywhere; genius is like light and air, the patrimony of all: cosmopolitan as space, as life and God.

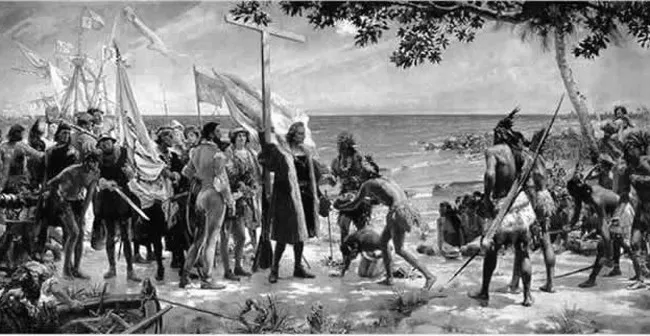

The Philippines' patriarchal era is passing, the illustrious deeds of its sons are not circumscribed by the home; the oriental chrysalis is quitting its cocoon; the dawn of a broader day is heralded for those regions in brilliant tints and rosy dawn-hues; and that race, lethargic during the night of history while the sun was illuminating other continents, begins to wake, urged by the electric' shock produced by contact with the occidental peoples, and begs for light, life, and the civilization that once might have been its heritage, thus conforming to the eternal laws of constant evolution, of transformation, of recurring phenomena, of progress.

This you know well and you glory in it. To you is due the beauty of the gems that circle the Philippines' crown; she supplied the stones, Europe the polish. We all contemplate proudly: you your work; we the inspiration, the encouragement, the materials furnished.

They imbibed there the poetry of nature-nature grand and terrible in her cataclysms, in her transformations, in her conflict of forces; nature sweet, peaceful and melancholy in her constant manifestation-unchanging; nature that stamps her seal upon whatsoever she creates or produces. Her sons carry it wherever they go. Analyze, if not her characteristics, then her works; and little as you may know that people, you will see her in everything moulding its knowledge, as the soul that everywhere presides, as the spring of the mechanism, as the substantial form, as the raw material. It is imposible not to show what one feels; it is impossible to be one thing and to do another. Contradictions are apparent only; they are merely paradoxes. In El Spoliarium -on that canvas which is not mute-is heard the tumult of the throng, the cry of slaves, the metallic rattle of the armor on the corpses, the sobs of orphans, the hum of prayers, with as much force and realism as is heard the crash of the thunder amid the roar of the cataracts, or the fearful and frightful rumble of the earthquake. The same nature that conceives such phenomena has also a share in those lines.

|

|

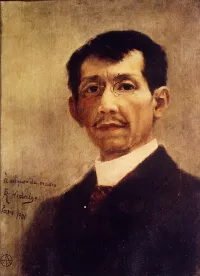

| Self portrait, Felix Resurreccion Hidalgo, 1901. |

Like sickly nurses, corrupted and corrupting, these opponents of progress pervert the heart of the people. They sow among them the seeds of discord, to reap later the harvest, a deadly nightshade of future generations.

But, away with these woes! Peace to the dead, because they are deadbreath and soul are lacking them; the worms are eating them! Let us not invoke their sad remembrance; let us not drag their ghastliness into the midst of our rejoicing! Happily, brothers are more-generosity and nobility are innate under the sky of Spain-of this you are all patent proof. You have unanimously responded, you have cooperated, and you would have done more, had more been asked. Seated at our festal board and honoring the illustrious sons of the Philippines, you also honor Spain, because, as you are well aware, Spain's boundaries are not the Atlantic or the Bay of Biscay or the Mediterranean-a shame would it be for water to place a barrier to her greatness, her thought. (Spain is there-there where her beneficent influence i"s exerted; and even though her flag should disappear, there would remain her memory-eternal, imperishable. What matters a strip of red and yellow cloth; what matter the guns and cannon; there where a feeling of love, of affection, does not flourish-there where there is no fusion of ideas, harmony of opinion?

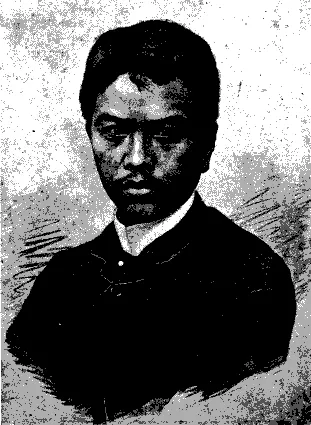

|

|

| Juan Luna |

But the Philippines' gratitude toward her illustrious sons was yet unsatisfied; and desiring to give free rein to the thoughts that seethe her mind, to the feelings that overflow her heart, and to the words that escape from her lips, we have all come together here at this banquet to mingle our vows, to give shape to that mutual understanding between two races which love and care for each other, united morally, socially and politically for the space of four centuries, so that they may form in the future a single nation in spirit, in duties, in aims, in rights. I drink, then, to our artists Luna and Hidalgo, genuine and pure glories of two peoples. I drink to the persons who have given them aid on the painful road of art!

I drink that the Filipno youth-sacred hope of my fatherland may imitate such valuable examples; and that the mother Spain, solicitous and heedful of the welfare of her provinces, may quickly put into practice the reforms she has so long planned. The furrow is laid out and the land is not sterile! And finally, I drink to the happiness of those parents who, deprived of their sons' affection, from those distant regions follow them with moist gaze and throbbing hearts across the seas and distance; sacrificing on the altar of the common good, the sweet consolations that are so scarce in the decline of life — precious and solitary flowers that spring up on the borders of the tomb.

Source

- Gems of Philippine oratory; selections representing fourteen centuries of Philippine thought, carefully compiled from credible sources in substitution for the pre-Spanish writings destroyed by missionary zeal, to supplement the later literature stunted by intolerant religious and political censorship, and as specimens of the untrammeled present-day utterances, by Austin Craig, page 34-37, University of Manila, 1924.