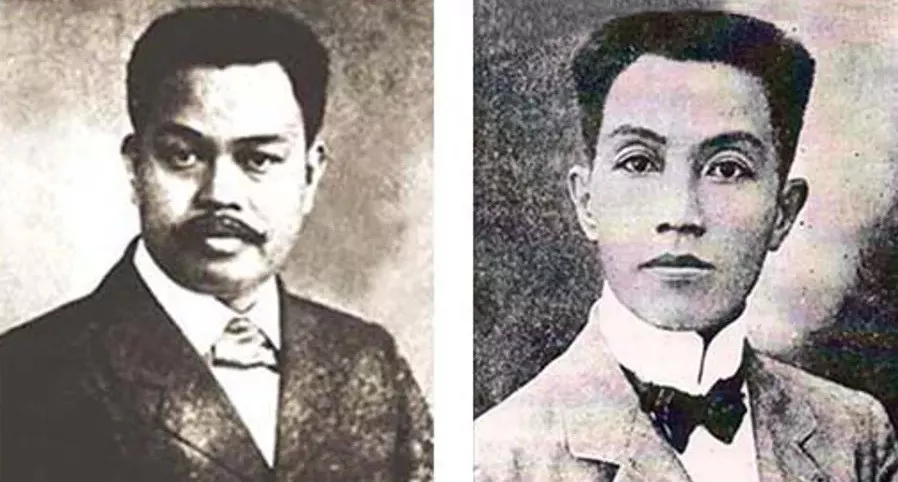

On June 5, 1899, General Antonio Luna was killed in the plaza of a rectory in Cabanatuan, Nueva Ecija. Luna was to attend a council of war called by General Emilio Aguinaldo.

Luna arrived with two aides-de camp and a mounted escort of twelve men. After dismounting and dismissing his escort, he proceeded alone to the rectory where Aguinaldo had his headquarters. On mounting the stairs, he was met by a junior officer, who informed him that Aguinaldo had left with his command. Luna felt slighted and expressed himself very strongly on the matter and prepared to take his departure. As he turned to leave the room, a sergeant of one of the two companies that Aguinaldo had left at Cabanatuan, sprang from behind the door, where he had been concealed, and attacked Luna from behind, inflicting a severe wound with a bolo.

General Luna, seeing himself surrounded and realizing that he was practically in the same strait as Andres Bonifacio had been at Naic, some three years previously, drew his revolver to defend himself. Not wishing to be overcomed by numbers in a hand to hand struggle in the rectory, he forced his way through his assailants and rushed down stairs into the plaza to summon his escort to his assistance. On arriving in the plaza, he was confronted by one of the companies that Aguinaldo had left in Cabanatuan to arrest him at all costs. The officer in command, judging that Luna, if arrested alive, would only be a source of embarassment to Aguinaldo, ordered his men to fire a volley. Luna fell at the first discharge but did not die before he wounded a number of assailants with his revolver.

Earlier, on about March or April, 1899, there were some overtures between Emilio Aguinaldo, Felipe Buencamino, and Pedro Paterno on the one hand and the American authorities on the other, towards a compromise on the basis of an autonomous government. It is unknown with whom these overtures originated, but Aguinaldo was disposed to listen to them. General Antonio Luna heard of this and, at a cabinet meeting at Cabanatuan, reproached the dictator with wishing to betray the "extreme" party. It was this party, according to Luna, which represented the people at large. It certainly did represent the majority of the Filipino leaders and Katipuneros who had gone into the field to fight for complete independence. They would be satisfied by no such half measure as autonomy.

The conversation became heated. Luna, who had a violent temper, threatened to kill Aguinaldo. The latter, however, managed to avoid an encounter just then. But Luna followed up and struck Buencarnino in the face. Buencamino then made his escape with Pedro Paterno and both took refuge in a stable.

To Aguinaldo, compromise or no compromise, autonomy or complete independence, there was not sufficient room in the Philippines for himself and General Luna. He thereupon determined to lay a trap and rid himself of the violent patriot for once and all. To this end he summoned General Luna to attend a council of war at Cabanatuan.

References

An army officer's Philippine studies, Captain John Young Mason Blunt, University Press, Manila, 1912